A Hand Holding a Tally Container

This post is a story of the four kanji that came from the a tally container and a hand of a celestial record keeper: 史, 事, 吏 and 使.

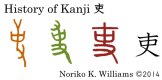

(1) 史 “history; to chronicle”

It all started with the images of a container that had bamboo sticks inside used as tallies, and a hand. A calendar maker kept the records of celestial changes using these tallies. The kanji 史 meant “to chronicle; history.” Throughout the three ancient writing styles, oracle bone style, in brown, and bronze ware style, in green, and even in ten style, in red, a container and a hand were recognizable as such. In kanji, something changed. I will come back to this shortly. The kanji 史 is used in words such as 歴史 (“history” /rekishi/) and 世界史 (“world history” /sekaishi/) in on-reading. There is no kun-reading.

It all started with the images of a container that had bamboo sticks inside used as tallies, and a hand. A calendar maker kept the records of celestial changes using these tallies. The kanji 史 meant “to chronicle; history.” Throughout the three ancient writing styles, oracle bone style, in brown, and bronze ware style, in green, and even in ten style, in red, a container and a hand were recognizable as such. In kanji, something changed. I will come back to this shortly. The kanji 史 is used in words such as 歴史 (“history” /rekishi/) and 世界史 (“world history” /sekaishi/) in on-reading. There is no kun-reading.

(2) 事 “work/job; thing; matter”

For the kanji 事, in oracle bone style, other than a twig shape at the top, it was the same as that of (1) 史. The twig shape was a sign where government work was done. It meant “work; job; thing; matter.” In bronze ware style, the first two writings had an additional wiggly sideway line right below the twig shape. This was a streamer to point out that it was the government office too. The third bronze ware style writing was less elaborate. In ten style, a hand that was more dominant and it intersected the vertical line that went through the bottom. In kanji, the vertical line goes up at the bottom. The kanji 事 is used in 仕事 (“work; job” /shigoto/) in kun-reading, 用事 (“errand” /yooji/) and 事件 (“incidence” /ji’ken/) in on-reading.

For the kanji 事, in oracle bone style, other than a twig shape at the top, it was the same as that of (1) 史. The twig shape was a sign where government work was done. It meant “work; job; thing; matter.” In bronze ware style, the first two writings had an additional wiggly sideway line right below the twig shape. This was a streamer to point out that it was the government office too. The third bronze ware style writing was less elaborate. In ten style, a hand that was more dominant and it intersected the vertical line that went through the bottom. In kanji, the vertical line goes up at the bottom. The kanji 事 is used in 仕事 (“work; job” /shigoto/) in kun-reading, 用事 (“errand” /yooji/) and 事件 (“incidence” /ji’ken/) in on-reading.

(3) 吏 “government worker”

The kanji 吏 means “government worker.” We see that the oracle bone style writing and the bronze ware style writing were essentially identical with those of 事 in (2) — “Government work” and “a person who works” used the same writing. In ten style, however, 吏 and 事 became different in that the vertical line did not go through in 吏. Further, in kanji the vertical line became a long bent stroke, which left only a single slanted stroke. The kanji 吏 is in 官吏 (“public servant” /ka’nri/). There is no kun-reading.

The kanji 吏 means “government worker.” We see that the oracle bone style writing and the bronze ware style writing were essentially identical with those of 事 in (2) — “Government work” and “a person who works” used the same writing. In ten style, however, 吏 and 事 became different in that the vertical line did not go through in 吏. Further, in kanji the vertical line became a long bent stroke, which left only a single slanted stroke. The kanji 吏 is in 官吏 (“public servant” /ka’nri/). There is no kun-reading.

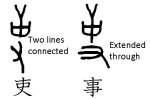

During the last few weeks, while I was preparing for the new kanji tutorial site videos, I was wondering how 史, 吏 and 使, our next kanji, had ended up with a bent stroke, whereas 事 had stayed with as a straight line. Here is my conjecture (the images on the left). When the vertical line in the container got connected to one of the strokes in hand, it produced the shape in 史, 吏 and 使. On the other hand, in 事 “work; job; matter” because a hand was an important aspect of doing actual work, it was made more recognizable. The vertical line in the container got extended through the hand and thus we got 事. Does it make sense to you?

During the last few weeks, while I was preparing for the new kanji tutorial site videos, I was wondering how 史, 吏 and 使, our next kanji, had ended up with a bent stroke, whereas 事 had stayed with as a straight line. Here is my conjecture (the images on the left). When the vertical line in the container got connected to one of the strokes in hand, it produced the shape in 史, 吏 and 使. On the other hand, in 事 “work; job; matter” because a hand was an important aspect of doing actual work, it was made more recognizable. The vertical line in the container got extended through the hand and thus we got 事. Does it make sense to you?

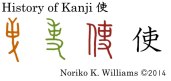

(4) 使 “to use; to make someone do; send a person as a proxy”

In the kanji 使, a bushu ninben was added to 吏 “government worker.” A bushu ninben always added the sense of “an act that a person does.” From “to make someone do the work,” 使 meant “to use” or “to send someone as a proxy.” It is used in words such as 使う (“use” /tsukau/) in kun-reading, 使用中 (“in use; occupied” /shiyoochuu/) and 大使 (“ambassador” /ta’ishi/) in on-reading.

In the kanji 使, a bushu ninben was added to 吏 “government worker.” A bushu ninben always added the sense of “an act that a person does.” From “to make someone do the work,” 使 meant “to use” or “to send someone as a proxy.” It is used in words such as 使う (“use” /tsukau/) in kun-reading, 使用中 (“in use; occupied” /shiyoochuu/) and 大使 (“ambassador” /ta’ishi/) in on-reading.

So, even though it started with a celestial record keeper, we do not seem to have received a visit from a space alien like we did in the posting last week. The writings were for mundane every day work and nothing fanciful. In the next post, if I can, I would like to take a break from a kanji story and touch on the topic of Japanese tonal patterns, which is very important for us to be able to speak correctly. [April 20, 2014]

Thank you

LikeLike