Jann Haworth: The forgotten creator of the Sgt. Pepper cover

17 May 2017

Peter Blake is celebrated as the creator of the sleeve art of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album. But his collaborator has been forgotten. As Sgt Pepper turns 50, ALASTAIR McKAY talks to American Pop artist Jann Haworth about art, celebrity, sexism, and her role in a modern design classic.

It would be wrong to suggest that Jann Haworth is annoyed about the fact that her contribution to the design of one of the most famous record sleeves in history has been airbrushed from history.

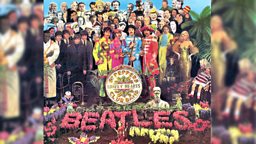

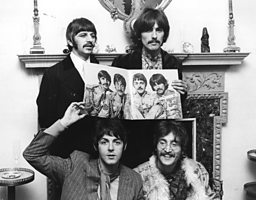

Haworth, along with her then-husband, Peter Blake, designed the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and as the 50th anniversary of the record’s release (on June 1st, 1967) approaches, others are stepping forward to highlight their own contribution to the image.

The pop art sleeve is commonly considered to be by Blake alone, with Haworth’s contribution marginalised

In a recent Mojo magazine, Nigel Hartnup, assistant to photographer Michael Cooper, suggested that it was he who pressed the camera shutter. An undated sketch – actually, a doodle – reputedly by John Lennon, is currently up for auction, which seems to suggest that he came up with the concept, though more often Paul McCartney is credited with drawing the original design.

Beyond these disputed details, the pop art sleeve is commonly considered to be by Blake alone, with Haworth’s contribution marginalised.

“In a way, it’s a patchwork vision that’s being put forward,” Haworth says, diplomatically. “And some of the things are in utter conflict.”

It’s true that Haworth’s reputation has suffered, largely because of her decision to prioritise family life over her artistic career. Some of this is just straightforward sexism, an outgrowth of the attitude she encountered when she asked a tutor at London’s Slade art school whether he needed to see her portfolio.

“He said: ‘We don’t look at the portfolios of the female students. We just look at their photographs, ’cause they’re here to keep the boys happy.’”

But Haworth also stresses the importance of collaboration in art, an approach which ties in with her use of traditionally female skills. She pioneered soft sculpture, casting life-size figures in cloth (her Shirley Temple doll is on the right of The Beatles’ sleeve.) Consider also that the Sgt. Peppers’ cover is a study in celebrity, and Haworth – the daughter of Oscar-winning production designer Ted Haworth - was raised in Hollywood.

“I grew up watching Marilyn Monroe perform, or Dana Wynter in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and I was young enough that they were just adults, they weren’t any more interesting than anybody else. I remember my friends being impressed that I knew Tony Curtis, and saying it must be so wonderful to daydream about him. I couldn’t do it. Celebrity has always been a fiction to me.”

Coming out of Hollywood, it’s how I’ve always workedJann Haworth

What, then, is the truth of the Sgt. Peppers’ sleeve?

“Let’s start with the crowd. The crowd really is Peter’s idea. It’s not Paul’s. It arises out of Peter’s work directly. It’s part of what he did at the time. He did collage, he’d ask his students to paint their heroes.

“It’s a convention, the portrayal of a group of people that way, in rows. He likes always to go to the most traditional, obvious idea. That speaks to a nostalgic photograph. But what it becomes in this case is a falsification. We know immediately it’s false. That’s the interesting, surreal part of it. Peter wanted to do it as a collage.

“My vision was to do it as a set. And that is supported by my work at the time. Everything I did was life size, everything I did had a setting so I would create furniture around something or I would put a figure that I had made in a chair with a lamp, with a dog, with flowers. Coming out of Hollywood, it’s how I’ve always worked.

“My father was in town at the time, making Half a Sixpence with Tommy Steele, so I conferred with him. We looked at a set he was doing. He’d actually got in touch with (fairground artist) Joe Ephgrave, through me, to get a merry-go-round for the set, and Joe was the one who painted the drum skin. Joe was a friend of mine.

“So I collaborated with my dad on that, and what my dad did was, he said what you want to do is have a backlit photograph to be behind The Beatles so that it looks real. The cheat of two-dimensional photographs eliding into a front row of three dimensional things - that’s straight from Hollywood, straight from my father, straight from me. I saw my dad do it from the age of five. It’s fun and funny. So I absolutely claim that.

“The flowers: I hated the idea of lettering, or a graphic designer taking Peter and my artwork and slapping their lettering on it. Paul claims it was his idea to do the civic flower arrangement – not right.

We were standing in my studio when that idea came up. I suggested itJann Haworth

“We were standing in my studio when that idea came up. I suggested it. (Art dealer) Robert Fraser and Paul came out to the studio and they would have come on the Hammersmith flyover, and right past that was this little instal of succulents that made... I think at the time it was a clock. The idea of doing lettering like that, I just loved, so I suggested that as another form of lettering, besides the drum, that would keep the integrity of the cover.

“So it doesn’t matter whether that’s 20% of the cover or 50%... the authorship was definitely enhanced by Robert Fraser and Paul and their confirmation of the ideas that we put forward, but it wasn’t prefigured by Paul at all, despite his claims.”

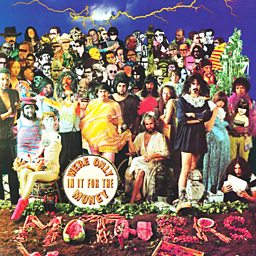

The continuing interest in the Sgt. Peppers’ sleeve has prompted Haworth to revisit and re-evaluate the image, and reference it in new works, first in SLC Pepper, a mural in Salt Lake City, Utah (where she now lives), which celebrated scientific advance rather than fame, and aimed for a cast that was 50% female.

It was followed in 2016 by Work In Progress (a collaboration with her daughter, Liberty Blake) which celebrated great female leaders. The work was commissioned to coincide with Hillary Clinton’s presidential candidacy and was translated into banners for the feminist protests during the Trump inauguration.

Haworth – who never listens to the Beatles – says she has taken more satisfaction from questioning the Sgt Peppers’ sleeve than she ever got from making the original artwork.

“It’s a piece of cardboard that’s a foot square. And you look at the photographs from the Hubble (space telescope), and you say, ‘How can it be important?’ It’s not like Rosalind Franklin’s photograph of DNA – or whether that was by Crick and Watson, or a collaboration. They looked at that, and then ‘bingo!’ something happened. Look what it’s done, that photograph, look what it’s done to medicine. That’s really big!”

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band was released on 1 June 1967.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms