Allen Jones is an easy artist to dismiss. In 2013 his images of women look regressive, to put it mildly. His 1969 work Chair is currently on view in the Tate exhibtion Art Under Attack, and plenty of visitors will sympathise with the feminist who once attacked this sculpture of a woman in high-heeled boots offering herself as a seat.

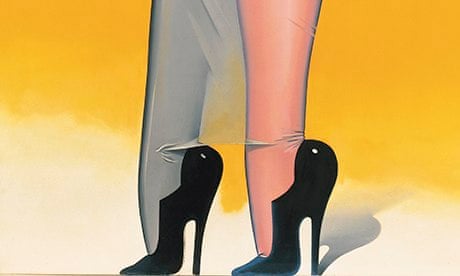

Yet, in his day, Jones was an artistic radical with a cool intellectual agenda. He's one of the stars of When Britain Went Pop!, a survey of the birth of British pop art at Christies' new gallery in Mayfair. His painting, First Step, in this show is, like Chair, so blatantly fetishistic that to say it objectifies women is a tautology: that is clearly what it sets out to do. Why?

The answer may come as a surprise to those who think the British discovered Marcel Duchamp in 1988 when a young Damien Hirst got lost in the Tate Gallery, wondered why the loo he was using was in a public place, and after a nasty scene learned he'd chanced on the art of the readymade.

Allen Jones was a Duchampian before the Hirst generation were even born. His art is an icy joke about the power of desire: it pays homage to Duchamp's ironic view of human culture as a masturbatory machine in his most ambitious work, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even.

In the early 1960s, Duchamp was the inspiration for a British artistic revolution. The leader of this movement and arguably the man who invented "pop" was Richard Hamilton – teacher, writer, painter and printmaker. Hamilton was an expert on Duchamp. He studied and "typotranslated" the Frenchman's complex notes, and created a replica of The Bride Stripped Bare so accurate Duchamp signed it as his work. This is the version the Tate owns.

Nowadays, it is Duchamp's urinal that's held up as an artistic inspiration for its bold statement that anything can be art. In 1960s Britain, however, it was the more complex allegory of The Bride Stripped Bare that struck artists as a brilliantly ironic portrait of modern life. It imagines the modern world as a consumerist cat-and-mouse game of endlessly frustrated desire.

As the consumer revolution got underway in Britain, and a new world of longing was opened up by TV and pop music, pop art portrayed the new age as a tantalising Duchampian comedy. Richard Hamilton's Hommage a Chrysler Corp slyly satirises the seduction of machines, while Jones gives the new sexual freedoms of the age a cynical absurdity.

British pop art is intelligent and ironic, and deeply skeptical about all it seems to celebrate. Its anthem, after all, is I can't get no satisfaction.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion